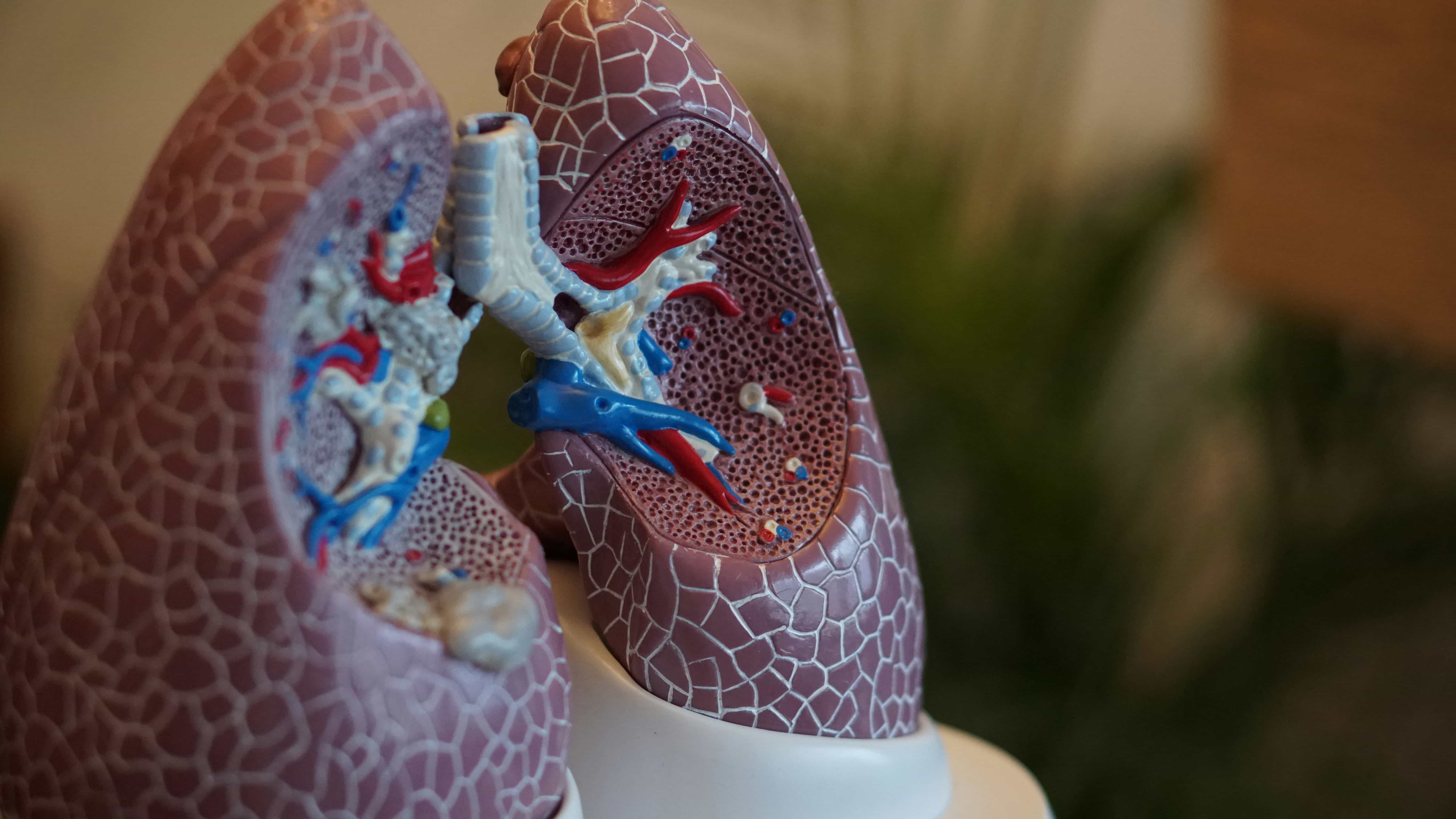

Radiation therapy is one of the most powerful tools for treating lung cancer. It works by damaging the DNA of cancer cells, preventing them from multiplying and eventually causing them to die. But not all cancer cells respond the same way. Some develop radiation resistance, meaning they become better at surviving treatment and continue to grow despite repeated exposure. This makes treating lung cancer much more difficult.

Scientists have now discovered a key reason why some lung cancer cells resist radiation. A specific gene called TRIP13 plays a major role in helping cancer cells repair their DNA more effectively after radiation exposure. The more TRIP13 a cancer cell produces, the better it can fix radiation-induced damage and the harder it is to kill. This discovery could lead to new treatments that block this resistance mechanism, making radiation therapy more effective for lung cancer patients.

The Hidden Weapon: How TRIP13 Helps Cancer Cells Survive

Cancer cells, like all cells, need functioning DNA to survive and multiply. Radiation therapy destroys cancer by causing double-strand breaks in DNA - essentially cutting the genetic instructions in half. Normally, when a cell’s DNA is damaged, the cell either repairs it or self-destructs to prevent harmful mutations. But some cancer cells have found a way to supercharge their repair process, allowing them to survive radiation that would normally kill them.

Researchers found that repeated exposure to radiation increases TRIP13 levels in lung cancer cells. This gene helps activate two key DNA repair pathways:

- Homologous Recombination (HR) – A highly accurate way for cells to repair broken DNA using an undamaged copy as a template.

- Non-Homologous End-Joining (NHEJ) – A faster but more error-prone method where broken DNA ends are stitched back together.

Cancer cells that produce more TRIP13 become better at fixing their DNA, meaning they can recover quickly from radiation damage. This allows them to continue growing and dividing, making treatment less effective.

What This Means for Cancer Treatment

The discovery of TRIP13’s role in radiation resistance is important because it gives doctors and scientists a new target for treatment. If TRIP13 can be blocked or reduced, cancer cells would struggle to repair their DNA after radiation, making them much easier to destroy.

Scientists tested this idea by removing TRIP13 from lung cancer cells and then exposing them to radiation. The results were clear - cells without TRIP13 were far more vulnerable to radiation, while those with high TRIP13 levels survived much longer. This means that blocking TRIP13 could be a potential strategy to make radiation therapy work better for lung cancer patients.

One promising approach involves TRIP13 inhibitors, drugs designed to shut down TRIP13’s ability to repair DNA. Early studies suggest that these inhibitors make lung cancer cells much more sensitive to radiation, potentially improving patient outcomes.

The Bigger Picture: How This Discovery Could Save Lives

Lung cancer is one of the most difficult cancers to treat, and radiation resistance makes it even harder. By understanding how TRIP13 helps cancer cells survive, scientists are now looking for ways to disrupt this process and increase the effectiveness of radiation therapy.

This discovery could have an impact beyond lung cancer. Other types of cancer, including head and neck cancers, breast cancer, and ovarian cancer, may also rely on TRIP13 to resist radiation. If researchers can find a way to safely block TRIP13, it could lead to better treatments for many different cancers.

The next step is testing TRIP13-blocking treatments in clinical trials to see if they work in real patients. If successful, this could lead to a major breakthrough in making radiation therapy more effective and improving survival rates for cancer patients around the world.

For now, scientists continue their work, uncovering the ways cancer fights back against treatment - and finding new ways to turn the tables and stop cancer in its tracks.