Every epidemic has a starting point - a moment when a virus, bacteria, or other infectious agent makes the jump into human populations and begins to spread. But by the time health officials detect an outbreak, the disease has often already moved far beyond its origin, making it extremely difficult to pinpoint exactly where and when it all began. Knowing this information is crucial. If scientists and policymakers could identify the first spark of an outbreak faster, they could act sooner and stop the disease before it spreads out of control.

A new study has developed a mathematical model to solve this problem. The researchers compare an epidemic’s early days to a Big Bang - an explosion of infections that grows exponentially. By studying the way diseases spread over time and space, they have created a system that can reverse-engineer an outbreak’s origins, allowing scientists to track where an epidemic likely started and how it traveled through different populations.

This breakthrough offers a powerful tool for public health officials. By applying this method in real-time, scientists could detect emerging outbreaks earlier, predict where a disease is heading, and prevent future pandemics from spiraling out of control.

Why It’s Hard to Find the First Case of an Epidemic

When a new infectious disease appears, it doesn’t announce itself immediately. In many cases, people who are infected early on don’t show symptoms right away, or their illness might be mistaken for something more common, like the flu. By the time enough cases are reported for officials to realize an outbreak is happening, the disease has often already spread to multiple cities or even countries.

The first documented case is rarely the true "patient zero." In reality, the outbreak likely began weeks or even months earlier. The challenge for scientists is working backward, using available data on infections, to reconstruct what actually happened.

Traditional methods of tracking outbreaks rely heavily on case reports and travel history, but these can be unreliable. If a disease spreads silently for a period of time before being noticed, key information can be lost, making it nearly impossible to pinpoint exactly where the outbreak began.

This study introduces a new way to approach the problem, one that doesn’t rely solely on case reports. Instead, it uses the movement of people and the way diseases spread between populations to mathematically estimate the most likely time and place of origin.

Using Math to Reverse-Engineer an Epidemic

The researchers created a metapopulation model to analyze how a disease spreads across different regions. Instead of looking at isolated outbreaks, they examined how populations are connected through travel and interactions, treating them as a network.

By studying infection patterns and the speed at which cases appear in different locations, the model rewinds the epidemic timeline, tracing the outbreak back to its most probable origin. The key innovation in this approach is something called effective distance, which takes into account not just physical location but how closely connected different areas are based on travel, trade, and human movement.

This method provides an accurate and scientific way to track epidemics, helping researchers piece together the missing details that case reports alone cannot provide.

Testing the Model on Real Epidemics

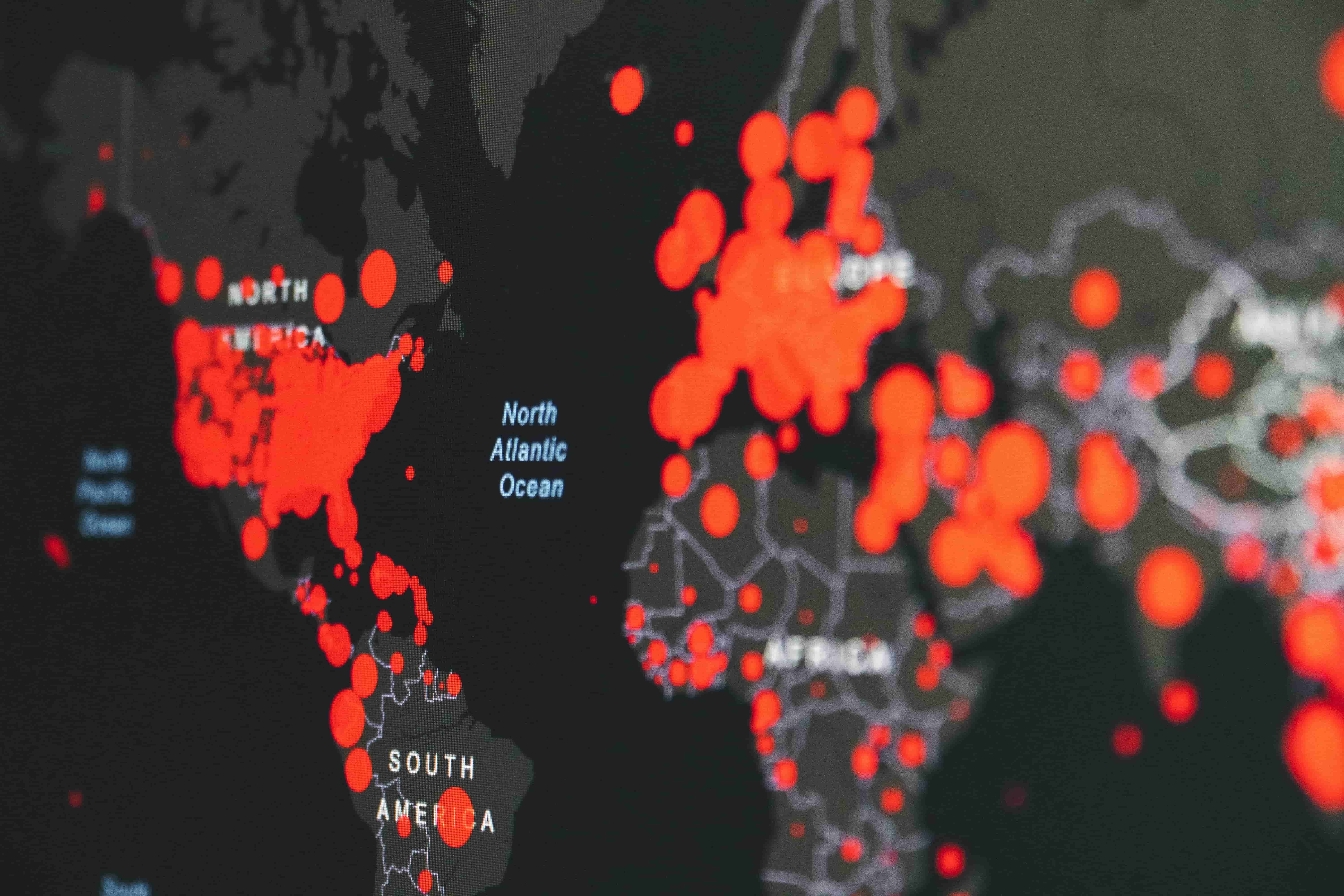

To prove that their method works, the scientists tested it on real-world outbreaks, including COVID-19 and the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic. In both cases, the model successfully identified the most likely origin of the outbreaks and was able to estimate how long the disease had been spreading before officials became aware of it.

For COVID-19, the model pinpointed Washington, New York, and Michigan as early outbreak zones in the United States.

When applied to the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic, the model correctly traced the origin of the outbreak to Mexico, showing how the disease spread globally along major air travel routes.

The consistency of these results suggests that all epidemics follow certain predictable patterns, regardless of the disease. This means the model could be used for future outbreaks of new diseases, helping health officials get ahead of the next pandemic.

Why This Matters for the Future of Disease Prevention

Being able to quickly determine where and when an epidemic starts could change the way governments and health organizations respond to outbreaks. With a model like this, officials would no longer have to rely on slow case reporting and incomplete travel history. Instead, they could use real-time data on disease spread to make more informed decisions.

If this model had been available in the early days of COVID-19, for example, it could have helped countries detect the outbreak earlier, implement travel restrictions before the virus spread globally, and distribute resources more effectively.

This research also highlights the importance of mobility networks, showing that disease outbreaks are rarely confined to a single location. Instead, they move along human travel patterns, which means that understanding how people move is just as important as understanding how a virus behaves.

A New Tool to Fight Future Epidemics

As new infectious diseases continue to emerge, scientists and policymakers need better tools to respond quickly and effectively. This new model offers a powerful way to track outbreaks in real time, allowing researchers to detect early warning signs before an epidemic grows out of control.

Beyond disease tracking, the methods developed in this study could also be used in other fields, such as tracing foodborne illnesses, misinformation spread on social media, or even cybersecurity threats.

By understanding how outbreaks begin and spread, scientists and public health officials have a better chance of stopping epidemics before they become global disasters. The “Big Bang” of an epidemic may be impossible to prevent entirely, but with the right tools, we can contain outbreaks before they explode into full-scale pandemics.